Brand Hierarchy Realities

In many scenarios, companies actually back in to their brand hierarchies. They churn out products and develop services based on their customers’ needs, or market gaps. This process happens in a vacuum, and can often be, uh, less than thoughtful.

As a result, those companies often find themselves trying to manage muddy, undefined, confusing hierarchies that neither internal or external stakeholders really understand. In the much-better-case alternative, a brand will think purposely about its goals and capabilities and THEN establish and support the hierarchy that makes the most sense.

That process begins with evaluation. Look at your brand. What do you do now? What do you want to do down the road? What do you excel at, and what makes you unique? How are your current brands positioned, how do they work together (or not), and what value does that add (or not)?

Next, review your options. Look at the hierarchies that are out there, and identify the one that’s most applicable to where your brand wants to go. Options differ on how many “official” hierarchies should be on the menu for your consideration; Defy frequently considers the following three:

- Branded House

- Hybrid

- House of Brands

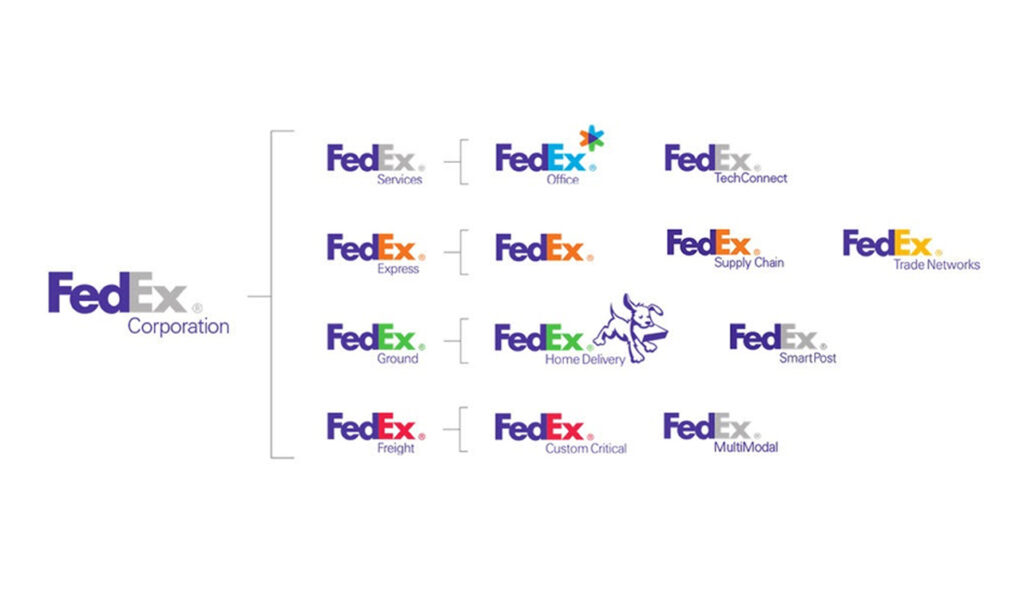

A branded house is the easiest to define: it’s a scenario in which all brands within the hierarchy look and feel related to the “parent” brand, and the parent adds equity to the sub-brands. It’s interconnected both visually and operationally–all brands look and feel closely related, and are aligned from a management perspective, increasing efficiency and cohesion on the back end.

A hybrid structure is the middle ground option–it incorporates a “branded house”-style setup but can incorporate and support strong, stand-alone brands that open up new markets (think Zappos and Amazon). The hybrid can be a best-of-both-worlds situation, increasing market share and allowing for dynamic acquisitions. That said, if you go this route, proceed with caution –companies utilizing this approach must be clear about their rules (for example, what qualifies a brand to stand “outside of the house”), and apply them consistently, to avoid finding themselves back in “muddy, undefined, and confusing” territory.

A house of brands structure is best for the “you do you” set – it allows all brands within the family to be themselves, lean in to their own strengths, and operate with degrees of independence not found in the branded house. For this reason, it’s pretty inefficient from a big picture perspective… but it maximizes each individual brand, and minimizes risk by eliminating super strong ties between the corporate brand and its relatives. For example, let’s look at two Unilever brands: if Axe Body Spray makes a bad PR move, will Dove foaming hand soap feel the burn? Definitely not.

Once you’ve got a handle on your options, and have identified the structure that will work best for your brand, the work begins. You develop it, establishing all relevant rules and systems–no easy task. Then, your brand must thoughtfully and consistently apply that framework, both operationally and creatively, to maximize the selected structure’s potential benefits.

Like anything else, a hierarchy shift–or even just a hierarchy reinforcement–is a heavy lift, requiring diligence and objectivity… and usually accompanied by more than a few late nights and heated discussions. If done correctly, however, it maximizes your brand and best-positions your business for growth and success.